F

P

Mar 19, 2024

Mar 19, 2024

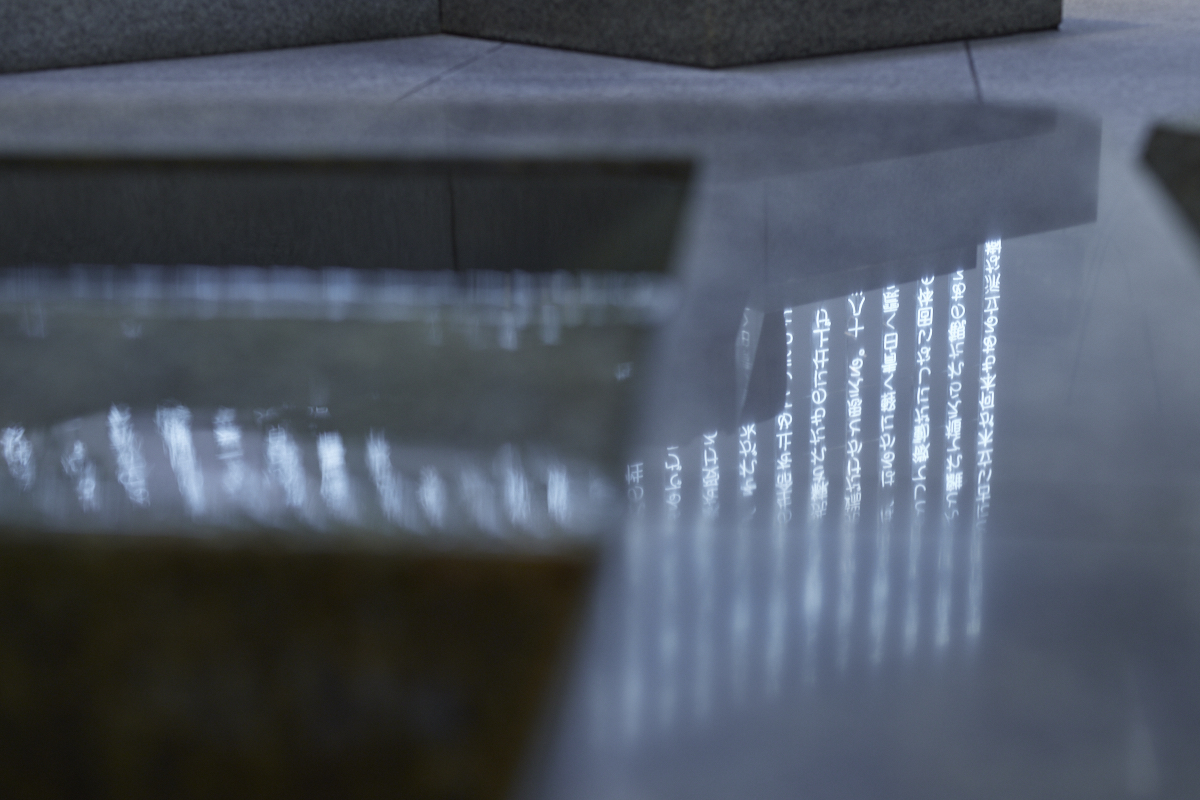

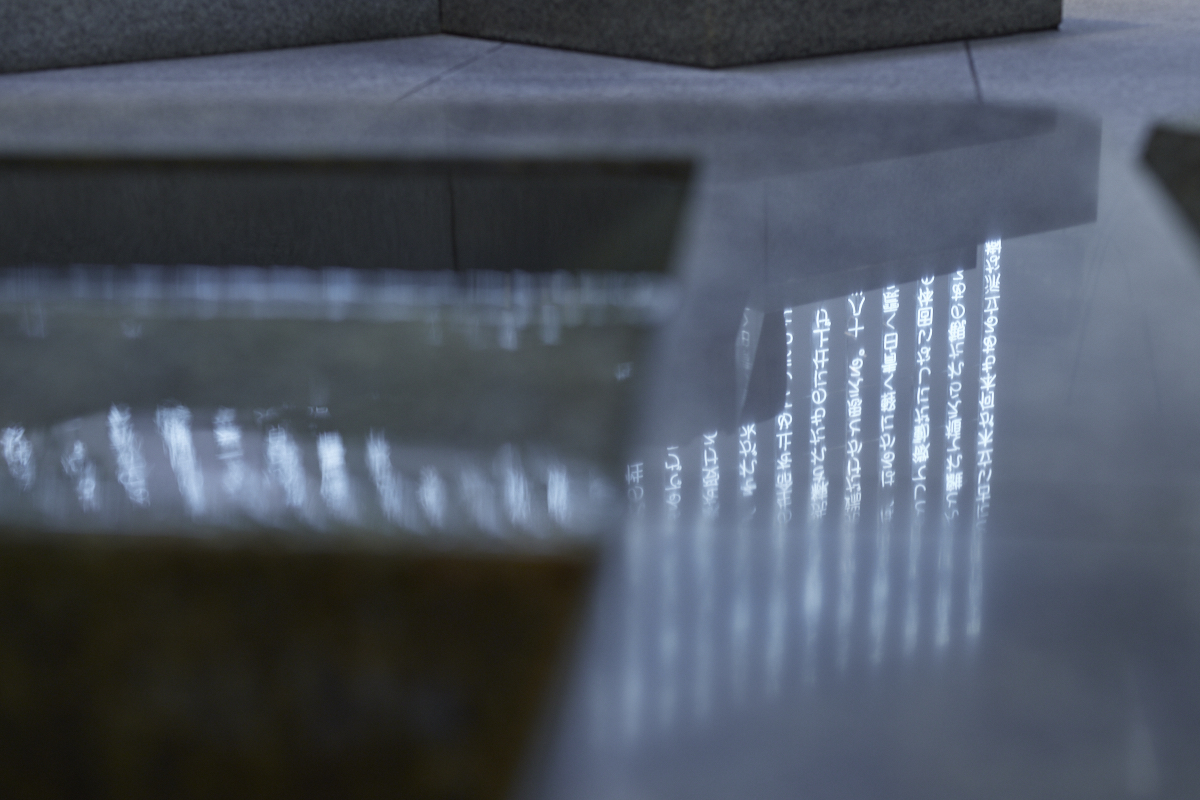

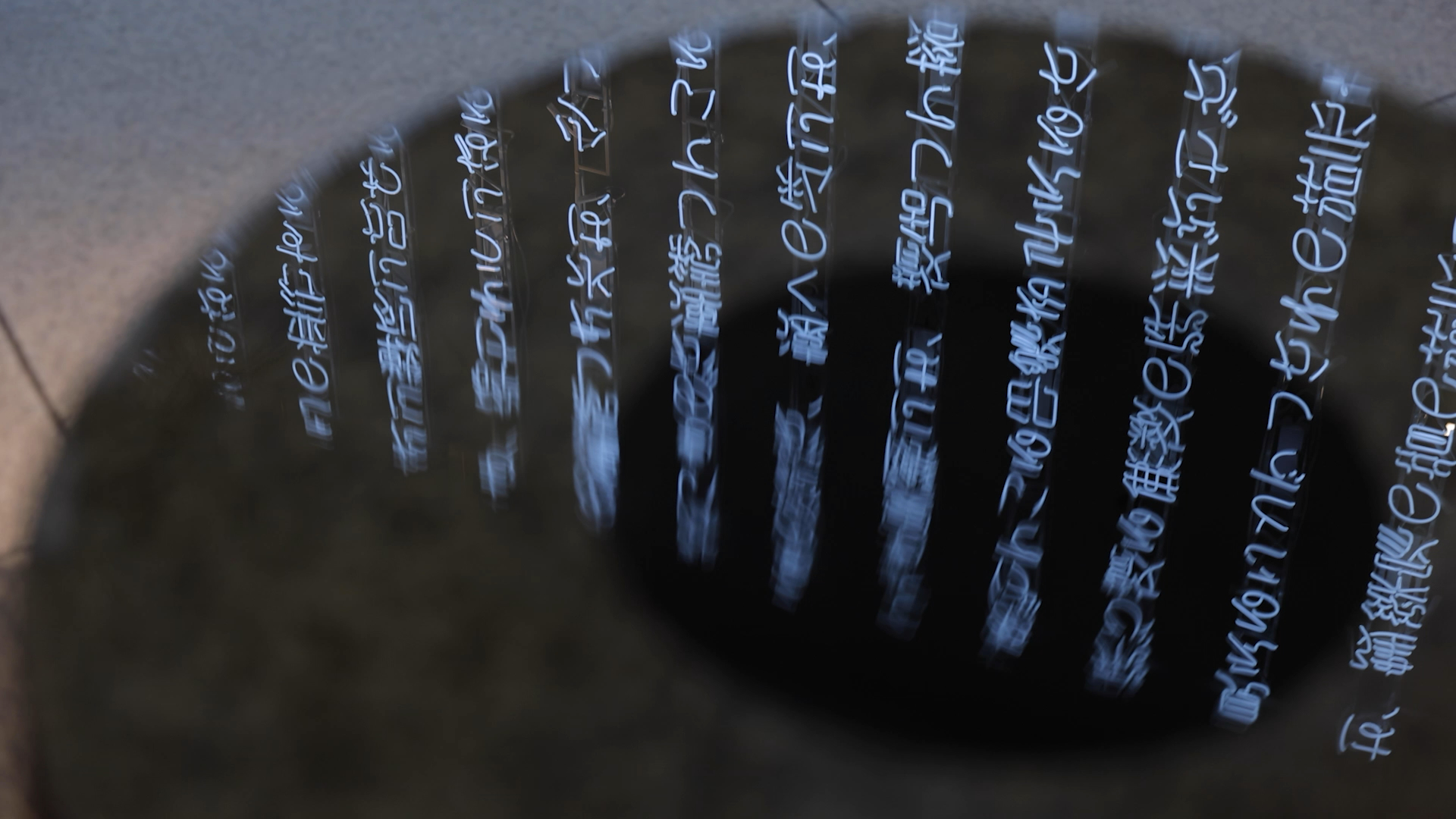

ケリス・ウィン・エヴァンス 展示風景 草月会館 1F 石庭「天国」(東京) 2023 年4月1日 – 29日 Courtesy of Sogetsu Foundation. Photo: Kenji Takahashi

Cerith Wyn Evans, installation view at stone garden "Heaven," the Sogetsu Kaikan, Tokyo, Apr 1-29. Courtesy of Sogetsu Founation. Photo: Kenji Takahashi

ケリス・ウィン・エヴァンス 展示風景 草月会館 1F 石庭「天国」(東京) 2023 年4月1日 – 29日 Courtesy of Sogetsu Foundation. Photo: Kenji Takahashi

Cerith Wyn Evans, installation view at stone garden "Heaven," the Sogetsu Kaikan, Tokyo, Apr 1-29. Courtesy of Sogetsu Founation. Photo: Kenji Takahashi

能「融」 山階彌右衛門 草月会館1F 石庭「天国」(東京) 2023年3月31日

Courtesy of the artists and Sogetsu Foundation. Movie: Kentaro Matsumoto

Noh “Toru,” Yaemon Yamashina; indoor stone garden “Heaven,” the Sogetsu Kaikan, Tokyo; Mar 31, 2023

Courtesy of the artists and Sogetsu Foundation. Movie: Kentaro Matsumoto

草月会館の「天国」とタカ・イシイギャラリー。2つのエヴァンスの作品空間で略式の能仕舞が演じられた。 オープニング時にあしらわれた『融』とクロージングを飾った『野守』である。

日本贔屓のエヴァンスの所望だったのかどうかは知らない。伝え聞いたところでは、下見のときにエヴァンスの光の柱が立つイサムノグチの草月会館の石庭が源融の河原院を想わせたので、能楽師の山階彌右衛門が『融』を選び、エヴァンスの鏡面仕上げに見える作品感覚が宝生流の佐野登に『野守』の鏡を連想させたからだったという。 見立てである。注1

見立ては日本文化の多くの入口ではあるが、出口ではない。見立てられたアイテムやシンボルを入口にしながら、どこか「あてどもないところ」へ出向いていくか、日々の「おもい」に立ち戻っていくか、そこをトークンとして摘んでみせるのが和歌や能や立花や俳諧や浮世絵をして見立てをおもしろくさせてきたところだった。 私は、このエヴァンスと能との出会いの映像だけを見せられて、主催者からその感想を後追いで求められただけなので、はたして、2つのパフォーマンスの見立てがエヴァンスの作品群をどのように支援できたのか(あるいは刺し違えられたのか)、その実感からはいささか遠いのだが、多少の感想は出入りしたので、そのことを述べておこうと思う。 まず二つのことを述べておく。

ひとつ。 映像を見て、オープニングとクロージングが「影向」によって挟撃されていることを感じた。 影向とは、何かのただならぬ気配から鬼神の近づきを予感あるいは察知することで、古今新古今の歌、中世の大和絵や絵巻,寺社の祭事にはしばしば用いられてきたモチーフである。 能ではこの察知をひときわ重視するので、いつしか舞台に「影向の松」や「橋かがりの松」を設えるようになったけれど、松が依代(よりしろ)や物実(ものざね)に選ばれたのは正月の松飾りや「囃」(はやし)でもおこなわれていたことである。 とくに怪異なことでもなく、また日本に特有のものでもない。 私はアルベルト・ジャコメッティの彫塑やフランシス・ベーコンの絵画などにも、たいてい影向を感じてきた。 エヴァンスの作品の多くにも影向は煌めいてきた注2。

ふたつ。 エヴァンスの作品空間に能があしらわれたのは、日本における展示会としては好ましいオマージュ的な選択だったとは思うものの、エヴァンスが秘めてきた多重性や批評性からすると、やや象徴に加担しすぎたように感じた。 今日の日本は劣化が進行しすぎているので、それならむしろ、かつてエヴァンスが気分を寄せたマルセル・ブロータースのような憤然たる社会批判や、さもなければこれまたかつてエヴァンスが従事していたデレク・ジャーマンの哀感ともなう最後通告こそ必要だろうと感じる。 映像を見るかぎりは、その手の「にがみ」からは逸れていた。 いやいや『融』や『野守』にも苦味はあるじゃないかと言うかもしれないが、残念ながら最近の演能にはそのへんは希薄なのである。

Seigo Matsuoka

Two improvisational Noh performances inspired by Cerith Wyn Evans’s works were staged in the indoor stone garden “Heaven” at Sogetsu Kaikan and at Taka Ishii Gallery in Tokyo. Toru was held to mark his exhibitions’ opening, and Nomori at their closing.

I do not know whether this was at the request of Evans, who is well versed in Japanese culture. As to the program choices, I heard that the Isamu Noguchi-designed stone garden at Sogetsu Kaikan illuminated by Evans’s pillar of light was reminiscent of Kawara-no-in, the villa of Minamoto no Toru, and this led the Noh actor Yaemon Yamashina to choose Toru. Meanwhile, the mirror-like finish of Evans’s works reminded Noboru Sano of the Hosho School of the mirror in Nomori. These are examples of mitate.note1

Mitate is the Japanese tradition of using metaphors, associations and double meanings in a playful manner. The core process of mitate involves treating one object not in the way it was originally intended but in another, and it serves as an entry point to many aspects of Japanese culture, though not as an exit. Once through the portal of repurposed items or symbols, the true allure of mitate in waka poetry, Noh, ikebana, haiku, or ukiyo-e lies in drifting from place to place without a destination, or in reverting to day-to-day thoughts and feelings, while picking and presenting these objects and symbols as tokens along the way. I was only shown performance videos of the encounters between Evans’s installations and Noh and was later asked by the organizers to share my thoughts. For this reason I feel somewhat removed from the actual experience of how the mitate of the two performances might have supported (or, for that matter, crossed swords with) Evans’s body of work. Nonetheless, I have formed some impressions, which I will now share, starting with two points.

First: watching the videos, I felt that the opening and closing were enfolded in the grasp of yogo. This spiritual term describes the eerie or awe-inspiring sense or premonition of the approach of demons or deities, and it is a frequent motif in classical waka poetry, medieval Yamato-e paintings and picture scrolls, and rituals at temples and shrines. Noh in particular embraces this sensation, which led to the adoption of yogo no matsu (the large pine tree painted on the backdrop of the main stage) and hashigakari no matsu (pine trees along the bridge leading to the main stage). The pine tree as yorishiro (object that attracts divine spirits) or monozane (symbolic item) is also reflected in Japanese New Year’s pine decorations and its inclusion in hayashi musical accompaniment, and it is neither particularly mysterious nor exclusively Japanese. Nor is yogo a specifically Japanese phenomenon––I have often sensed it in the sculptures of Alberto Giacometti and the paintings of Francis Bacon, and it similarly emanates from many of Evans’s works.note2

Second: while integrating Noh into the spaces containing Evans’s was an appropriate tribute to Japan on the occasion of an exhibition held here, it did have the effect of symbolically circumscribing the inherently multifarious and critical nature of his work. In light of Japan’s current precipitous decline, a more fitting approach might have been to present cutting social critiques like those of Marcel Broodthaers, whom Evans admired, or the elegiac ultimatums of Derek Jarman, with whom Evans worked. The videos I saw, at least, lacked such acerbic qualities. While one could argue that Toru and Nomori have acerbic aspects, unfortunately, these have been diluted in recent Noh performances.

さてそこで、ここからは私が見聞してきたエヴァンスの作品力の話になるのだが、私がエヴァンスを意識したのは高橋悠治のクセナキス研鑽をドキュメントしようとしていたあたりに始まっている注3。 その後、マラルメを追っているうちに、またデレク・ジャーマンを追っているうちに、そのいずれにもエヴァンスが顔を覗かせているのを知って、このアーティストのデーモンとゴーストの「ありか」に親近感をもつようになった。 ここでデーモンとゴーストと言ってみたのは、自分と他者がまじっていく関係を見守っているのがデーモンで、その他者によって自分の中に出入りするようになったものがゴーストだという意味なのだが、エヴァンスの日々においてはこのデーモンとゴーストの「ありか」がさまざまな作品に凝集していったのだった。 とくに初期に映像習作にとりくんだことは、このアーティストの多重多様なデーモンとゴーストのアリバイをさぐるのに有効だったのだろう注4。

一方、そのような「ありか」やアリバイがなんとガラス管やネオン管に逼塞するようになったことに、私は意外な昂奮をおぼえたものだ。 そこまで透明なニューロンや鏡面の血管にして大丈夫なのかと思ったが、心配することもなかった。 なにもかもがチューブになるなんて、いったいエヴァンスに何が兆したのだろうか。 LGBTQのQにあたるものもがチューブ化していったのではないか。そんなふうに思われる注5。 Qとは「変」ということ、「変」でかまわないということである。 私たちには作品群を通して「変としてのQ」は零れてきていた。 そういう見方からすると、エヴァンス展を迎えるにあたっては、日本の「クィア」をもって寿いでもよかったようにも思う。 たとえば、能に近い「翁」などをもって。

Now, to move on to my perceptions of the power of Evans’s works. I first became aware of Evans when I was documenting Yuji Takahashi’s piano renditions of the compositions of Iannis Xenakis.note3 Subsequently, as I was exploring the works of Stéphane Mallarmé and Derek Jarman, I discovered that Evans had connections to both. This led me to feel closer to the dwelling places of this artist’s demons and ghosts. Here, my use of the words “demons” and “ghosts” relates to the intertwining of self and other, with demons presiding over it, while ghosts are things that the other introduces and causes to drift in and out of the self. The dwelling places of demons and ghosts in Evans’ daily life have been aggregated in his diverse body of work. Notably, his early involvement in film likely aided in unraveling the myriad alibis of the demons and ghosts surrounding him.note4

It has been an unexpected thrill to witness how he somehow encapsulates these dwelling places and alibis in glass and neon tubing. I worried about whether it was prudent to render everything so transparent, like neurons or mirror-finished blood vessels, but my concerns were unfounded. Enclosing everything in tubes––what did this process symbolize for Evans? It is possible that something corresponding to the “Q” in LGBTQ is being encased in these tubes. This is my impression.note5 Of course, this Q stands for “queer,” a word with multiple meanings, but in any case it signifies pride in being unusual or different. It’s possible that for viewers such as myself, the “Q for queer” has been evident throughout his body of work. From this perspective, in holding Evans’s exhibition, it might have been appropriate to celebrate it with the “queer” qualities of Japanese culture––for example the performance of okina,note6 a unique aspect of Noh.

注釈

—

注1:松岡正剛『見立て日本』(角川ソフィア文庫)、松岡『日本文化の核心』(講談社現代新書)|back

注2:2015年10月26日・27日、渋谷パルコ劇場で『影向』を公演。田中泯・宮沢りえ・松岡正剛・山本耀司・石原淋出演。脚本・松岡。|back

注3:「遊」1973年7号「現代音楽の最前線」、高橋悠治「フィルター(数)・音のトランス装置」|back

注4:デーモンとゴーストについては、松岡正剛・津田一郎『科学と生命と言語の秘密』(文春新書)などを参照|back

注5:松岡正剛・千夜千冊エディション『性の境界』(角川ソフィア文庫)|back

note

—

note1: Seigo Matsuoka, Mitate to Nihon [Mitate and Japan], Kadokawa Sophia Bunko; Matsuoka, Nihon bunka no kakushin [The Core of Japanese Culture], Kodansha Gendai Shinsho|back

note2: On October 26 and 27, 2015, the play Yogo was staged at PARCO Theater. The cast included Min Tanaka, Rie Miyazawa, Seigo Matsuoka, Yohji Yamamoto, and Rin Ishihara. The script was by Matsuoka.|back

note3: Yuji Takahashi, “Filter [kazu] oto no trans sochi” [Filter (Number): Sound Trans Device], Yu no. 7, 1973, “Gendai ongaku no saizensen” [The Forefront of Contemporary Music].|back

note4: For more information on demons and ghosts, see Seigo Matsuoka and Ichiro Tsuda, Kagaku to seimei to gengo no himitsu [Secrets of Science, Life, and Language], Bunshun Shinsho.|back

note5: Seigo Matsuoka, Sei no kyokai [Boundaries of Sexuality] Senya Sensatsu Editions, Kadokawa Sophia Bunko)|back

note6: In Noh theater, performances are categorized into five distinct types based on their content: shin (deity), nan (man), nyo (woman), kyo (madness), and ki (demon). However, okina stands apart as a category apart from these, and as a sacred ritual traditionally performed before all Noh plays, it is the most extraordinary performance in all of Noh. The actor playing the role of okina takes the stage unmasked as a human being, then puts on the okina mask to symbolize the incarnation of a deity within. He then performs a dance invoking peace, prosperity, and bountiful harvests. The audience, as both participants and observers of the ceremony, are transported to another dimension.|back

「融」 あらすじ

旅の僧(ワキ)が都の六条河原の院で、汐汲みの老人(前シテ)と出会います。僧は海辺でもないのに汐汲みと名乗る老人をいぶかしく思います。すると老人は、六条河原の院とは、その昔、源融の大臣が陸奥の塩竈の浦を模して庭を作らせた場所であると教え、河原の院の謂われを語り、深い懐旧の念を表します。そして、京都の山々の名所を僧に教え、汐汲みの仕事を始めるかに見えた老人は、潮のしぶきに紛れて姿を消してしまいました。僧は、都の男(アイ)に六条河原の院の謂われと融の大臣について語るよう頼みます。僧から不思議な老人に出会ったことを打ち明けられた男は、その老人こそ融の大臣の霊であると言い、僧に弔いを勧めて立ち去ります。僧が旅寝をしていると、融の大臣の霊(後シテ)が現れ、月下のもとで舞い遊び、明け方となると月の都へと消え失せてゆきました。

————出典:「融」能サポ曲目解説、檜書店

A Traveling Monk from the Eastern Provinces visiting the Kawara-no-in Villa in the Rokujō area of the ancient capital (today Kyoto) meets an Old Man carrying water buckets. The Monk questions the Old Man, who claims to be drawing brine even if the sea is far from there. The Man explains how, long ago, the Minister of the Left, Minamoto no Tōru, wished to reproduce the famous scenery of the salt kilns of Michinoku right here in the garden of the Kawara-no-in Villa. As the Old Man talks, he reminisces the olden days at Kawara-no-in. Later, he shows the Monk various mountains surrounding Kyoto. Finally, the Old Man announces that he will start drawing brine, before disappearing in a cloud of sea spray. The Monk asks a Local Man to tell him the story of Minamoto no Tōru and of the Kawara-no-in Villa. When the Monk explains he just met a mysterious old man, the Local Man says that it must be the ghost of Minamoto no Tōru and urges the Monk to offer prayers in his memory. As the Monk falls asleep, the Ghost of Minamoto no Tōru appears in his court garb and dances under the moon, remembering the joys of the olden days. As dawn breaks, he disappears.

———Source: Summary of “Tōru” in NOH-sup, Hinoki Shoten.

ケリス・ウィン・エヴァンスは、自身もたびたび語るように、日本の伝統文化、とりわけ14世紀に大成された古典演劇である能に魅了されています。そして、15年前の来日時に草月会館(丹下健三設計)を訪れ、衝撃を受けたというイサム・ノグチによる石庭「天国」を舞台として2018年に個展を開催した際には、草月流いけばなの家元、勅使河原蒼風の思想に共鳴したと述べています。「天国」は、草月会館の1階と2階のオープンスペース約540平米の大空間を占め、さまざまな石肌の巨石とそれらを流れる水を配した5層からなる前衛的な石庭です。1960年代には旧草月会館の草月ホールにて「ジョン・ケージ、デイビッド・テュードア演奏会のイベント」(1962年)、ロバート・ラウシェンバーグによる「ローシェンバーグへの公開質問会」(1964年)、「マース・カニングハム・ダンス・カンパニー来日公演」(1964年)などの国際的なイベントが開催されました。2023年3月、エヴァンスはタカ・イシイギャラリーでの個展とともに、この「天国」での2回目の個展を実現しました。関係者を招いたオープニングイベントでは、「天国」を舞台に能楽師 山階彌右衛門が能「融」を、クロージングイベントではギャラリースペースを舞台に宝生流シテ方 佐野登が一噌流笛方 一噌幸弘とともに能「野守」を披露しました。本号のFun Palaceでは、「天国」で非公開に上演した能「融」全編映像をアーカイブとして公開します。

「天国」での個展で展示された作品《F=O=U=N=T=A=I=N》(2020年)は、高さ約4メートル、幅約11 メートルの白色ネオンで構成された大型の作品です。ネオンで描かれた漢字のテキストは、プルーストの『失われた時を求めて』第4篇「ソドムとゴモラ」の日本語訳 注 より引用されています。それは、太陽の光で華やかに逆光に照らされて、半透明のしずくを落とす噴水を描写する一節です。この作品の前には、床面から天井に達する3本の光の柱が緩やかな周期で明滅を繰り返し、能舞台の設えにならった3本の松の木がそれと気づかないほどのゆっくりとした速さで回転しています。そして、37本のクリスタルガラス製のフルートとコンプレッサーで構成される、自動演奏作品「Composition for 37 flutes」(2018年)がアルゴリズムに基づき、能の囃子方の笛のように会場内に和音と不協和音を奏でます。ネオンの壁は一部が門のように開かれ、草月会館のガラスの開口部へ、その向こうの外界へと繋がり、観客の視線を誘います。

《F=O=U=N=T=A=I=N》は、ロンドンのWhite Cubeで2020年に最初に発表されました。展覧会を訪れた大多数の観客がこの漢字で描かれたネオンのテキストを判読できなかったことは容易に想像ができます。今回東京に展示された同作品を多くの観客は読むことができます。それでもテキストの壁を目の前にして、彼らは言葉の意味を探そうと立ち尽くすことになったでしょう。しかし、インスタレーション空間の中で時間が経過するにつれて、しだいに深呼吸をするような振動や音の周期、作品の周囲の影や行き交う人々の影、設けられた空間の裂け目、水面に映る柱の光の残像、磨き上げられた石の表面を流れる水音、それらの揺らめく反射と反響が呼び起こす広がりが、石庭「天国」をある種の超感覚的な空間に変換していきます。記号としての言語の意味は薄れていき、舞台は光と影、内部と外部、現実と非現実、それらの「間」にある幻想的な領域を生じさせます。

エヴァンスは、隠喩、抽象が多用される能からの影響を語っています。能は約650年の歴史をもつ、具象を徹底して排することで物語の生成を観客に委ねる舞台芸術です。オープニング・レセプションにおいてエヴァンスの作品を舞台に上演された能「融」は、月というイメージを詞章や動きにさまざまに絡めて、平安時代の左大臣、源融の霊がその邸宅、河原院の廃墟で月夜に舞う姿を描いています。クロージング・レセプションで上演された「野守」には、天界から地獄の底まで映し出す水鏡が此岸と彼岸との境界としてあらわれます。能の演技は、すべて型という様式に律せられ、舞は最小限の動きが凝縮されています。喜怒哀楽といった感情表現すら様式化され、抽象的、象徴的な型と融合しています。物語の設定を問わず、あらゆる場面すべてが一本の老松を背景に演じられ、写実を排して最小限の象徴的な小道具のみが舞台上に置かれます。「微かな暗示」という能を構成している要素が、無への想像力を刺激して観客それぞれの解釈を堪能させるのです。エヴァンスの作品もまた、知覚と知覚の間にある領域を作り出し、私たちが世界について知っていると思っていることや、それを知覚する方法の儚さを伝え、観客に解釈を委ねます。エヴァンスの作品と能 – それらが邂逅した上演は、新しいクリエイションの胎動となるかもしれません。

———注:出典:マルセル・プルースト作/吉川一義訳『失われた時を求めて 8』(岩波文庫、2015年刊 pp136-138より抜粋)|back

Cerith Wyn Evans has frequently discussed his fascination with Japan’s traditional culture and particularly with classical Noh theater, which attained its fully realized form in the 14th century. During a visit to Japan 15 years ago he was captivated by the Isamu Noguchi-designed stone garden “Heaven” at Sogetsu Kaikan (building designed by Kenzo Tange), and he had a solo show in the space in 2018. Evans has described this exhibition as resonating with the philosophy of Sofu Teshigahara, founder of the Sogetsu School of ikebana flower arrangement. “Heaven,” occupying a large open space of approximately 540 square meters spanning the first and second floors of Sogetsu Kaikan, is a five-level avant-garde stone garden comprising boulders of various textures and water flowing among them. In the 1960s, Sogetsu Hall at old Sogetsu Kaikan was the venue for such international events as John Cage and David Tudor’s performance for the “Sogetsu Contemporary Series” (1962), Twenty Questions to Bob Rauschenberg featuring Robert Rauschenberg (1964). In March 2023, Evans held his second solo exhibition in “Heaven” concurrently with a solo show at Taka Ishii Gallery. At an invitation-only opening event, Yaemon Yamashina, a Noh actor, performed the Noh play Toru at the stone garden. At a closing event, Hosho School Noh shite (main performer) Noboru Sano appeared in the Noh play Nomori at the gallery. As the Noh play Toru was not open to the public, Fun Palace has archived and released videos of the performance.

Evans’s F=O=U=N=T=A=I=N (2020), presented at “Heaven,” is a large and striking white neon work, measuring approximately four meters in height and 11 meters in width. A wall of neon kanji characters spells out a quotation from a Japanese translation of Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, volume 4, Sodom and Gomorrah,1 describing a fountain that drips translucent droplets splendidly illuminated by sunlight. At the exhibition, in front of this work were three pillars of light extending from floor to ceiling, pulsating in a gentle rhythm, with three pine trees inspired by the backdrop of a Noh stage rotating at an almost imperceptibly low speed. Meanwhile, Composition for 37 flutes (2018), an automated musical sculpture comprising 37 crystal glass flutes and an air compressor system, filled the space with algorithmically generated music, by turns harmonious and discordant, that resembled Noh’s hayashi musical accompaniment. A section of the neon wall was open like a gate leading to a glass door in the Sogetsu Kaikan wall, drawing viewers’ gazes outward and connecting them with the external environment.

F=O=U=N=T=A=I=N was first unveiled in 2020 at White Cube in London. One can assume that most visitors were unable to read the neon kanji text, while in Tokyo, it was legible to the majority of viewers. Nonetheless, they were probably inclined to ponder the words’ significance as they stood before the text-laden wall. Over time, vibrations and sounds evocative of deep breathing emerged and filled the installation space, combining with the shadows around the work and those of passersby, crevices in the space, afterimages of the luminous pillars reflected on the water’s surface, the sound of water cascading over polished stones, and shimmering reflections and quavering echoes to transform the stone garden “Heaven” into a supersensory realm. The role of language as a signifier of meaning dwindled, giving way to a fantastical domain of light and shadow, internal and external, real and surreal, and the interzones between them.

Evans has spoken of the influence of Noh, a performing art rich in metaphor and abstraction. Over its 650-year history, Noh has rigorously avoided direct representation and entrusted the construction of narratives to the audience. The Noh play Toru, staged at the opening reception in the space produced by Evans, introduces diverse interpretations of the moon into its verses and choreography while representing the ghost of the Heian period (794-1185) statesman Minamoto no Toru dancing in the moonlight amid the ruins of his residence, Kawara-no-in. In Nomori, presented at the closing reception, a mirrored pond reflecting everything from the heavens to the underworld becomes a threshold between this life and the next. Each movement in Noh adheres to a strict form, with dances reduced to a minimum of motion. Even the expression of emotions such as joy, anger, sorrow, and delight is stylized and melded into abstract, symbolic patterns. Regardless of the story’s setting, every scene unfolds against the backdrop of a solitary ancient pine tree with only minimal symbolic props placed on stage, thoroughly avoiding realism. Noh narratives are constructed from subtle hints that spark the imagination while turning it toward the void, encouraging the audience to savor their personal interpretations. Evans’s art similarly generates spaces between perceptions, conveying the ephemeral nature of our understanding of the world and our modes of perception and leaving interpretation open to viewers. The intersection of Evans’s work and Noh may herald the inception of a truly new form of creation.

———Note: Source: Marcel Proust, trans. Kazuyoshi Yoshikawa, In Search of Lost Time 8, Iwanami Bunko, 2015, pp. 136 – 138

ケリス・ウィン・エヴァンス 展示風景 草月会館 1F 石庭「天国」(東京) 2023 年4月1日 – 29日 Courtesy of Sogetsu Foundation. Still image from the movie: Kentaro Matsumoto

Cerith Wyn Evans, installation view at stone garden "Heaven," the Sogetsu Kaikan, Tokyo, Apr 1-29. Courtesy of Sogetsu Foundation. Still image from the movie: Kentaro Matsumoto

ケリス・ウィン・エヴァンス

—

[会期] 2023年4月1日[土]— 4月29日[土] ※終了しました

[会場] 草月会館1F 石庭「天国」

[特別協賛] ロエベ財団

[協力] ルイナール(MHD モエ ヘネシー ディアジオ)、草月会

—

能「融」

山階彌右衛門

[日時] 2023年 3月31日[金] オープニング・レセプション

[会場] 草月会館1F 草月プラザ 石庭「天国」

Cerith Wyn Evans

—

[Dates] Apr 1 – 29, 2023 *This Exhibition has already finished.

[Location] Stone garden “Heaven,” the Sogetsu Kaikan 1F

[Lead sponsor] LOEWE FOUNDATION

[Support] Ruinart (MHD Moët Hennessy Diageo) and Sogetsu Foundation

—

Noh “Toru”

Yaemon Yamashina

[Dates] Opening reception, Mar 31, 2023

[Location] Stone garden “Heaven,” the Sogetsu Kaikan, Tokyo

ケリス・ウィン・エヴァンス

「Green Room w/ attendant mirrors…」(tarrying with Kagami-ita)

—

[会期] 2023年4月1日[土]— 4月28日[金] ※終了しました

[会場] タカ・イシイギャラリー(complex665)

—

能「野守」

佐野登 (宝生流シテ方) 一噌幸弘 (一噌流笛方)

[日時] 2023年4月28日[金] クロージング・レセプション

[会場] タカ・イシイギャラリー(complex665)

Cerith Wyn Evans

“Green Room w/ attendant mirrors…” (tarrying with Kagami-ita)

[Dates] Apr 1 – 28, 2023

[Location] Taka Ishii Gallery (complex665)

—

Noh “Nomori”

Sano Noboru (Shite, Hosho school), Isso Yukihiro (Fue, Isso school)

[Date] Closing reception, Apr 28, 2023

[Location] Taka Ishii Gallery (complex665)

ケリス・ウィン・エヴァンス

—

[会期] 2018年4月13日[金]— 4月25日[水] ※終了しました

[会場] 草月会館1F 石庭「天国」

[協力] 草月会、獺祭

—

能「井筒」

山階彌右衛門

[日時] 2018年4月12日[木]

[会場] 草月会館1F 草月プラザ 石庭「天国」

能「井筒」

坂口貴信

[日時] 2018年4月20日[金]

[会場] 草月会館1F 草月プラザ 石庭「天国」

Cerith Wyn Evans

[Dates] Apr 13 – 25, 2018

[Location] Stone garden “Heaven,” the Sogetsu Kaikan 1F

[Support] Sogetsu Foundation, DASSAI

—

Noh “Izutsu”

Yaemon Yamashina

[Dates] April 12, 2018

[Location] Stone garden “Heaven,” Sogetsu Kaikan, Tokyo

—

Noh “Izutsu”

Takanobu Sakaguchi

[Dates] April 20, 2018

[Location] Stone garden “Heaven,” Sogetsu Kaikan, Tokyo

[会期] 2024年1月31日[水]— TBD

[会場] カールス教会(ウィーン)

[URL] https://www.erzdioezese-wien.at/karlskirche

ケリス・ウィン・エヴァンス

[会期] 2024年11月1日[金]— 2025年4月21日[月]

[会場] ポンピドゥー・センター・メス

[URL] https://www.centrepompidou-metz.fr/en/programme/exposition/cerith-wyn-evans

[Date] January 31, 2024 – TBD

[Location] Karlskirche, Vienna

[URL] https://www.erzdioezese-wien.at/karlskirche

Cerith Wyn Evans

[Date] November 1, 2024 – April 21, 2025

[Location] Centre Pompidou-Metz

[URL] https://www.centrepompidou-metz.fr/en/programme/exposition/cerith-wyn-evans

ケリス・ウィン・エヴァンス

1958年 ウェールズ スラネリ生まれ。

現在、ロンドンを拠点に活動。

—

ネオンを用いたテキスト作品に代表される、文学、映画、美術、天文、物理など幅広い分野における先人達の先駆的な試みを引用した作品や、内包された物質と非物質という両義性により鑑賞者の知覚を問い直す、光や音を用いた立体作品で知られる。 人という主体が知覚する経験や行為をも物理的な作品とみなし、作品を展示する空間やその空間の運営主体である組織のありようも作品の一部と考えるエヴァンスの姿勢は、理論・慣習・教育によって強固に形成された世界の輪郭を、豊かな知性をもって拡張する行為だといえる。

主な個展として、草月会館(東京、2023 年・2018 年)、アスペン美術館(2021 年)、ポーラ美術館(神奈川、 2020 年)、ピレリ・ハンガービコッカ(ミラノ、2019 年)、タマヨ美術館(メキシコ・シティ、2018 年)、 テート・ブリテン・コミッション(ロンドン、2017 年)、Museum Haus Konstruktiv(チューリッヒ、2017 年)、Museion(ボルツァーノ、イタリア、2015 年)、サーペンタイン・ギャラリー(ロンドン、2014 年)、 Bergen Kunsthall(ベルゲン、ノルウェー、2011 年)、バラガン邸(メキシコ・シティ、2010 年)、カステ ィーリャ・イ・レオン現代美術館(2008 年)、パリ市立近代美術館(2006 年)などが挙げられる。主なグル ープ展として、ミュンスター彫刻プロジェクト(2017 年)、ヴェネチア・ビエンナーレ国際美術展(2017 年)、モスクワ・ビエンナーレ(2011 年)、愛知トリエンナーレ(愛知、2010 年)、「万華鏡の視覚:ティッセン・ボルネミッサ現代美術財団コレクションより」森美術館(東京、2009 年)、横浜トリエンナーレ (2008 年) 、イスタンブール・ビエンナーレ(2005 年)、ウェールズ代表として参加したヴェチア・ビエンナーレ国際美術展(2003年)などに参加している。

Cerith Wyn Evans

Born in 1958 in Llanelli, Wales

Currently lives and works in London

—

Evans, as represented by his text works that employ the use of neon, is recognized for creating works that bear citations to the pioneering efforts of predecessors across a diverse range of cultural and academic spheres such as literature, film, art, astronomy, and physics; in addition to three-dimensional works that appropriate light and sound as a means to interrogate the “viewer’s” perception through the ambiguity of inherent materiality and immateriality. Evans’ approach that regards even the experiences and actions perceived by a person as the physical work, as well as considering the space in which the work is exhibited and the organizational conditions of the entity operating the space to also play an integral role, can indeed be considered as an act that extends the contours of our world strictly formulated by theory, custom, and education through a rich sense of wit and intelligence.

His major solo exhibitions include the Sogetsu Kaikan, Tokyo (2023 and 2018); the Aspen Art Museum, Aspen (2021); the Pola Museum of Art, Kanagawa (2020); Pirelli HangarBicocca, Milan (2019); the Museo Tamayo, Mexico City (2018); the Tate Britain Commission, London and the Museum Haus Konstruktiv, Zurich (both 2017); the Museion, Bolzano, Italy (2015); the Serpentine Gallery, London (2014); the Bergen Kunsthall, Norway (2011); Casa Luis Barragán, Mexico City (2010); the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Castilla y León (2008) and the Musée d’art moderne de la ville de Paris (2006). Evans has participated in numerous international group exhibitions including Skulptur Projekte Münster, Germany and the 57th Venice Biennale (both 2017); Moscow Biennial (2011); Aichi Triennale, Nagoya (2010); The Kaleidoscopic Eye. Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary Collection,” Mori Art Museum, Tokyo and Yokohama Triennale (2008); Istanbul Biennial (2005); and represented Wales at the 50th Venice Biennale (2003).

松岡正剛

1944年 京都生まれ。

現在、東京を拠点に活動。

—

編集工学研究所所長、イシス編集学校校長。武蔵野ミュージアム館長。

70年代にオブジェマガジン「遊」を創刊。80年代に「編集工学」を提唱し、編集工学研究所を創立。 その後、日本文化、芸術、生命科学、システム工学など多方面におよぶ研究を情報文化技術に応用し、メディアやイベントを多数プロデュース。 著書に『知の編集工学』(朝日新聞出版、2023年)、 『フラジャイル』(筑摩書房、2005年)、 『日本文化の核心』(講談社、2020年)、 『ルナティクス』(中央公論新社、2005年)、 『見立て日本』(KADOKAWA Future Publishing、2022年)、 『松岡正剛の国語力』(東京書籍、2023年)、 『科学と生命と言語の秘密』(文藝春秋、2023年)(津田一郎氏との共著)ほか多数。

Seigo Matsuoka

Born in 1944 in Kyoto,

Currently lives and works in Tokyo

—

Matsuoka is executive director of the Editorial Engineering Laboratory (EEL), known for research and development in information culture and technology. He is also president of ISIS (Interactive System of Inter Scores) Editorial School and Director of the Kadokawa Culture Museum in Tokyo. He founded the popular arts magazine Yū in the 1970s. In the 1980s he developed a unique methodological worldview, which he calls “editorial engineering” and established the Editorial Engineering Laboratory. Since then he has applied his wide-ranging research on Japanese culture, art, life sciences, systems engineering and other fields to information culture and technology, producing numerous media and events. Major published works include Editorial Engineering (Asahi Shimbun Publications, 2023), Matsuoka Seigo no kokugoryoku [The Power of Seigo Matsuoka’s Language] (Tokyo Shoseki, 2023), Kagaku to seimei to gengo no himitsu [Secrets of Science, Life, and Language] (with Ichiro Tsuda) (Bungeishunju, 2023), Mitate Nihon [Mitate Japan] (KADOKAWA Future Publishing 2022), Nihon bunka no kakushin [The Core of Japanese Culture] (Kodansha, 2020), Fragile (Chikumashobo, 2005), and Lunatics (Chuokoron-Shinsha, 2005).