F

P

Apr 20, 2021

Apr 20, 2021

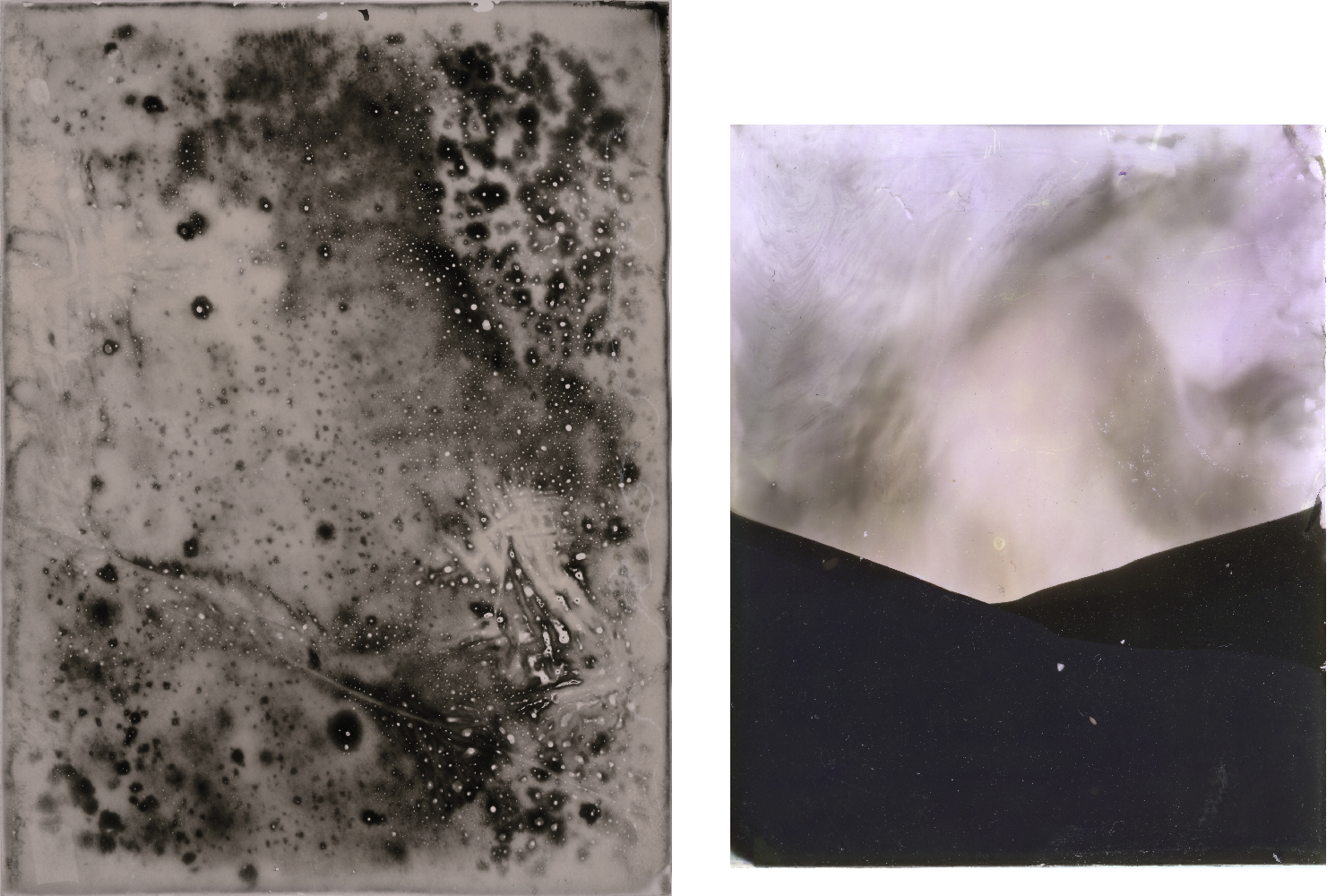

left| Hanako Murakami, “Untitled (Fitch’s negative xylonite films #1), 2021, Vintage photographic film, 17.8 x 23.8 cm

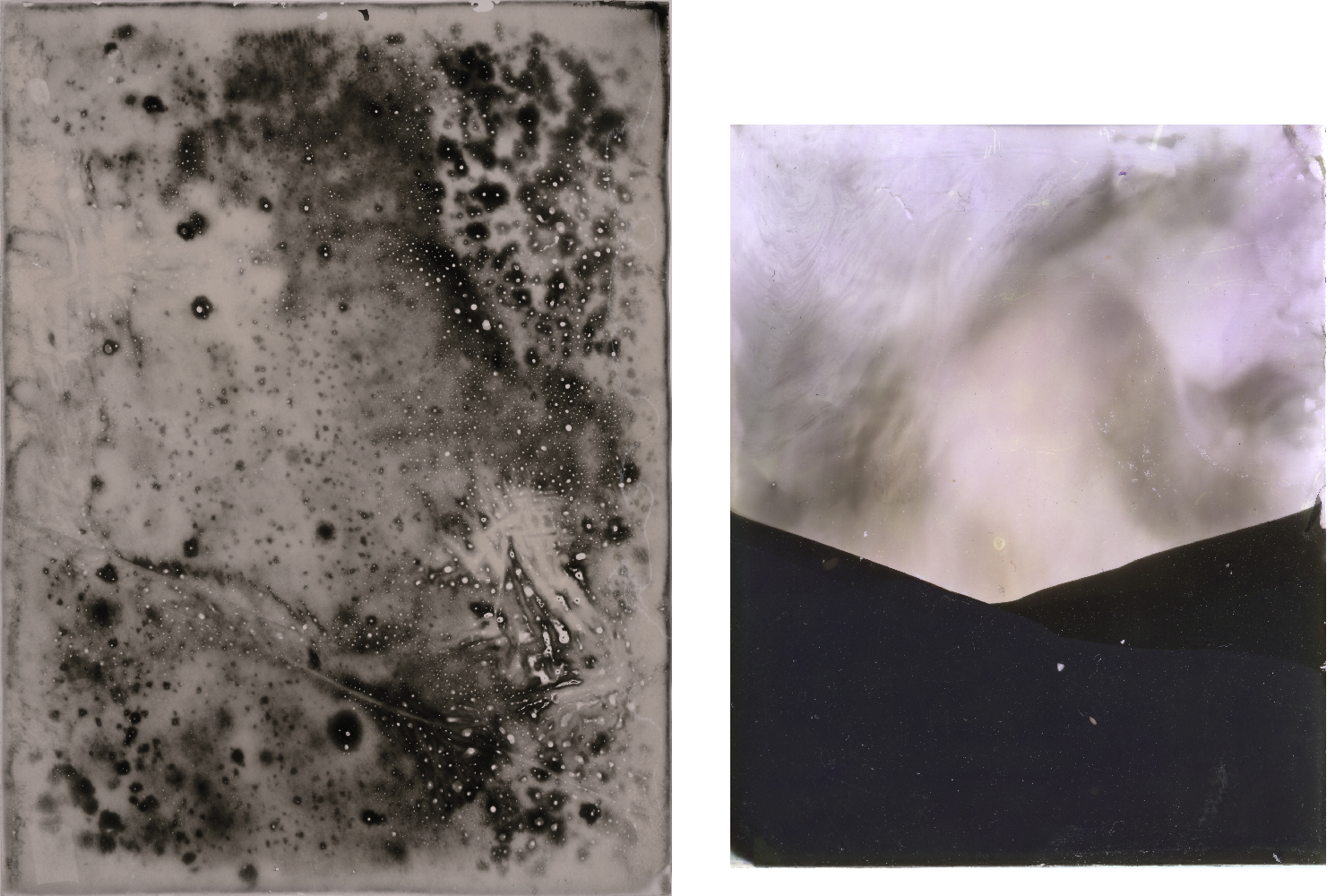

right| Hanako Murakami, “Untitled (Eastman lantern slide plate #3), 2021, Vintage photographic glass plate, 8.2 x 10.1 x 0.1 cm

left| Hanako Murakami, “Untitled (Fitch’s negative xylonite films #1), 2021, Vintage photographic film, 17.8 x 23.8 cm

right| Hanako Murakami, “Untitled (Eastman lantern slide plate #3), 2021, Vintage photographic glass plate, 8.2 x 10.1 x 0.1 cm

left| Hanako Murakami, “Untitled (Fitch’s negative xylonite films #1), 2021, Vintage photographic film, 17.8 x 23.8 cm

right| Hanako Murakami, “Untitled (Eastman lantern slide plate #3), 2021, Vintage photographic glass plate, 8.2 x 10.1 x 0.1 cm

left| Hanako Murakami, “Untitled (Fitch’s negative xylonite films #1), 2021, Vintage photographic film, 17.8 x 23.8 cm

right| Hanako Murakami, “Untitled (Eastman lantern slide plate #3), 2021, Vintage photographic glass plate, 8.2 x 10.1 x 0.1 cm

最初のロックダウンが始まってから丸一年が経った。一昨日からはフランスで三度目のロックダウンがはじまった。最初のロックダウンに比べると制約はややマイルドになったが、やはりこの一年のほとんどを家の中で過ごしたような実感がある。

家で一年間じっとしていると、その分時間が経つのが遅くなるかのようである。あるいは、逆に速くなるのかのようである。ともあれ、ともかく、家で過ごす二度目の春がめぐってきて、まだ肌寒いのに桜っぽい花が窓の外に見えたりもする。

2020年は全人類が家の中に閉じこもって、全ての活動が停滞し、文化活動の大部分が中止や延期の憂き目にあう、と言ったらその前の年まで誰も信じなかっただろう。しかし実際にはそういうことが起きて、今もその事態を私たちは生きている。

これまで家の外で行われてきたあらゆる活動がラップトップの小さな画面の中で擬似的に行われるようになり、作品を発表することもその例外ではない。今回のこのオンラインマガジンというものもその一環である。私たちはこのことをどう捉えるべきだろうか。

わたしは自宅の暗室にこもって、百年も前から未使用の写真印画紙を現像液の中に浸していた。傷みの激しいものは丸ごと現像して、嵐が吹き荒れるような情景になる。そうでもないものは、現像液にうまい具合に浸して山々のような情景を浮かび上がらせる。これらの印画紙も、ほんとうならもっと遠くを旅して、異国の光景を持ち帰ってくるはずだったのかもしれない。

暗室の赤色灯の色はそういえば、目を閉じたまま太陽を見たときに見える色に似ている。わたし達は本来、まぶたを閉じれば、いつでもどこでも、限りなく自由なはずだ。

It has now been a full year since the first lockdown began. In France, the third lockdown went into effect the day before yesterday. Restrictions are a bit looser than the first time, but I still feel like I’ve spent almost the entire past year at home.

I spent this year at home, and sometimes it feels like the less you move around, the more slowly time passes. On the other hand, staying still can make time seem to go by faster. In any case, my second spring spent sitting at home is on its way, and while it’s still chilly, I can see flowers resembling cherry blossoms outside my window.

Up until 2019, no one would have believed that 2020 would see the bulk of humanity shut up in their homes, the world grinding to a halt in so many ways, and the majority of cultural activities canceled or postponed. But that is what happened, and we are still living through it now.

All the things I used to do away from home are now simulated on the small screen of my laptop, and exhibiting my work is no exception. This online magazine is part of that. How should we deal with these circumstances?

I have been holing up in the darkroom at home soaking photographic paper, untouched for 100 years or more, in developing solution. When the severely damaged ones are fully developed, it produces vistas resembling raging storms. Others emerge from the fluid as what appear to be mountainous landscapes. These pieces of photographic paper may have been intended to be taken on long voyages and bring back scenes of foreign lands.

The red light of the darkroom is like what you see when you look at the sun with your eyelids closed. By all rights, when we close our eyes, anytime and anywhere, we ought to find total freedom.

Hanako Murakami

Vintage film reels developed by the artist in 2020 (top to bottom):

Ciné-Kodak, Kodak, 1944, United States

Special film, Geveart, circa 1940, Belgium

Hanako Murakami

Vintage film reels developed by the artist in 2020 (top to bottom):

Ciné-Kodak, Kodak, 1944, United States

Special film, Geveart, circa 1940, Belgium

|1|

神谷幸江 写真が瞬間を撮りおさめることができる、という得意技にむしろ目を向けず、言い換えればあなたの眼が何を目の当たりにしたかよりも、フィルムや印画紙がどれほどの時間を経て、何を見てきたのか、華子さんの作品は浮き上がらせようとしているようです。あなたにとっての写真について、時間について聞かせてください。

村上華子 写真はこれまで多くの場合「決定的瞬間」と結びつけられてきました。しかし実際の時間は、決定的ではない時間の方が多く、そんな緩やかな時間の方が私たちの人生の時間であると言えるでしょう。時間を仮に棒状の物として捉えるとすると、決定的瞬間はそれに楔を打ち込むようなものです。写真として残っている過去の光景は、楔の部分だけを見て残りの棒を想像する「よすが」のようだということになります。

また、写真を撮る時の私たちの振る舞いの不自然さについていつも気になっていました。写真がそこにあるということは、ある瞬間にある場所で誰かがカメラを取り出して、これぞ、という時にわざわざシャッターを切った結果です。しかし一つの空間におけるカメラの出現、というのは非常にわざとらしい、不自然なことです。カメラの存在によって突如、ここにいない人にもこの光景が見られることになり、知らない他者の視線が闖入してくるからです。水温を測ろうとして水温計を入れたら水温が変わってしまった、という時のように、カメラというのは実は全くニュートラルな装置ではないと思っています。

それでは、決定的ではない瞬間、楔を打ち込まれる前の棒のような時間を捉えるには、と考えた時に、これまで撮られなかった無数の写真について考えようと思いました。わたしの作品では、100年、あるいは150年以上前の、未使用の写真材料が用いられています。

これらは使われるはずだったが未使用のまま使用期限の切れた商品、である以上に製造の時点から現在に至るまで、撮られたかもしれないのに撮られなかった無数の写真の集積でもあると思ったのです。

|1|

Yukie Kamiya It seems that you do not pay some much attention to the usual focus of photography – the specialized skill of capturing a scene instantaneously. In other words, you are fascinated with exploring the history of the film and the photographic paper – how long it has existed, and been exposed to the passing of time. Could you please tell us about the importance of time in your conception of photography?

Hanako Murakami We often associate photography with “decisive moments,” but the moments we experience in real life tend not to be decisive, that is, the time that makes up the vast majority of our lives is time that creeps by gradually. If we think of time as a long, continuous tubular kind of structure, those decisive moments are like sharp wedges driven into it at certain points. The scenes of the past that endure as photographs are like mnemonic devices, showing us those wedge-points and enabling us to extrapolate the rest of the tubular time-tunnel from them.

Another thing that has always concerned me is the unnatural way people behave when their photograph is being taken. When we see a photograph, it is the result of someone taking out a camera at a specific moment and clicking the shutter because they thought “this is something to remember.” However, the very fact of the camera being in that space makes the whole process highly planned-out and unnatural. Because of the presence of the camera, suddenly the eyes of strangers are on us, suddenly people who were not there can see the scene. In my view, a camera is actually not a neutral device at all, it’s like a thermometer that changes the temperature of the water when it’s stuck in the water to take that temperature.

So, when I was thinking about how to capture non-decisive moments, the moments that make up the long tube of time when it’s not disturbed by a wedge being driven in, I thought of the countless photographs that have not been taken. My work makes use of unused photographic materials that are 100, sometimes 150 years old.

These are products intended for use that have gone unused and are long past their expiration date, but more than that, I think of them as an accumulation of the myriad photographs that went untaken from the time of their manufacture until now.

|2|

神谷 華子さんの「テキスト」の試みについてお話ください。

写真と組み合わせ、テキストを度々書き下ろしていますね。イメージとテキスト、この2つはどのような関係を築いているんでしょうか(「詩」と言ったほうがいいですか?)

村上 言葉にすることは息をするようなものですが、作品を作るにはものに息をさせる必要があります。違うことをしているようで、同じことをしていると思います。

一方で、言葉そのものが作品になることもあります。一昨年のアルル国際写真フェスティバル注1で発表した《Nomenclature》は、写真という概念そのものの誕生にまつわる作品で、photography という語が誕生する以前に写真を指していた語を並べたものでした。その時、語そのものに存在の厚みを持たせようと一つひとつの言葉を鉛で鋳造して、ずっしりと重いものにしました。その時の出来立ての鉛の言葉には燃えるような熱がありました。ものが液体から固体に状態が遷移するときのように、元は同じものでもイメージからテキスト、テキストからイメージ、へと姿が変わる時に熱が発生するのかもしれません。

|2|

Kamiya What is the role of text in your practice? You often write texts that accompany your photographic work. What kind of relationship do you hope to create between the image and the text (or as it were, poetry)?

Murakami Putting thoughts into words is like breathing, but then to make a work of art, you also need to make things breathe. So these two things, text and photography, look like they’re doing two different things but it’s actually the same process.

On the other hand, text or words themselves can become works. Nomenclature, which I presented at Les Rencontres d’Arles note two years ago, is a work relating to the birth of photography as a concept, and it consists of a list of words used to refer to photography before the word “photography” was coined. Each word was cast in lead to make the words themselves thicker and heavier, to give each one a more powerful presence. When the words had just been freshly cast in molten lead, they gave off incredible heat. It may be that heat is generated when things change from image to text, text to image, even if they were originally the same thing, like when matter changes state from liquid to solid.

|3|

神谷 パンデミックに見舞われた時期、ならばオンラインという空間をオルターナティブスペースと見立てて取り組んだならば、どんな表現が可能か、というチャレンジを掲げてプロジェクトをご一緒しました。その際、華子さんはオンラインならではのテクスチャーがある、と言っていましたね。ヴァーチャルな空間で作品を見せる/展示することを通じてどんな発見がありましたか?

村上 ロックダウンの初期、Zoomミーティングが流行り始めた頃のジョークに「Zoomは降霊術だ」というものがありました。ミーティングに接続して、

「聞こえますか?」

「みんないますか?」

「ちょっと聞こえづらいようですね」

「それでは始めます」

といった一連のやりとり、あるいは返事の不在、あるいはノイズが、19世紀末に流行した降霊術、またはチャネリングを始めるときの流れと同じだというのです。実体として、フィジカルに目の前にいない存在との対話、という共通点からの発想でしょう。しかしそれ以上に示唆的なのは、パンデミックで人々がロックダウンされインターネットという時間と空間のポテンシャルを徐々に見出していった時に、集合的想像力の中へ目に言えないものの存在が介入してきたということです。

インターネット上の空間というのは、実際の空間のではなく、数学と物理の粋を尽くしたプログラミング言語による仮想空間で、独自の秩序と論理で動いています。その空間を現実空間に似せて利用することも可能ではありますが、無理に似せるとかえって不自然になり仮想空間の貧困さが際立ってしまいます。しかし、それで仮想空間が貧困だ、と思ってしまうのは誤解で、その独自の秩序と論理をうまく使って作品を作るポテンシャルは確かに存在する、と思っています。

昨年のフランスの第一回のロックダウン中に、CNAP(国立造形芸術センター)の呼びかけでImage3.0 というプロジェクトの公募がありました。ジュ・ド・ポーム美術館との共催で、イメージをめぐる最新のデジタル技術を用いた、完全に脱物質化された作品、という条件の公募でした。パンデミックが今後どのような形で収束を迎えるにしても、近い将来の展覧会を考える時に作品の輸送も人の移動も従来のようにはいかず、さまざまな制約が課されることを見越したプロジェクトです。美術館もぜんぶ閉まってしまって身動きの取れない現状を逆手に取っているといえるでしょう。私は、テレビゲームで用いられるアイトラッキングのカメラを利用して、画面を見た時に、見た部分だけ燃え上がる、という作品を提案しました。それが採用され、現在制作中です。視線、という古くからその存在を信じられてきた不可視のものを、デジタル技術によって実体を与える試みです。

など、話が遠回りになりましたが、ジャパン・ソサエティーのウェブサイトのための4つの作品も、展示空間のとしてではなくウェブならではの表現をできるように作ったつもりです。実際の展示空間ではいくら近づいても見えないくらい、作品の高精細スキャンをしてどこまでも拡大できるようにしたり、テキストにマウスオーバーで画像が出たり、映像が縦に連なったり重なりあったり、とささやかながらウェブならではの「テクスチャー」を生かしたつもりです。

|3|

Kamiya During the unforeseen pandemic, we worked together on a project exploring a virtual platform as an alternative space, looking into what kind of artistic practice might be possible in this situation. At the time, you said that there is a kind of texture unique to online environments. What kind of discoveries did you make by presenting and exhibiting your work in a virtual space?

Murakami In the early days of the lockdown there were jokes going around about how a Zoom meeting was like a séance. People join a meeting, and the conversation at first goes like:

“Can you hear me?”

“Are you there?”

“I’m having trouble hearing you…”

“All right, let’s begin.”

And sometimes there’s no answer, or there’s some kind of interference. So it’s like when people were trying to contact the departed, or channel some spirit, during the late 19th-century spiritualist craze. This reflects the fact that, in practice, both a Zoom meeting and a séance are dialogues with entities that are not physically present. But what’s even more interesting is the idea of invisible presences intervening in the collective imagination, as occurred when people were stuck indoors during the pandemic and gradually discovered more of the temporal and spatial potential of the Internet.

Of course cyberspace isn’t really space, it’s virtual space produced with programming languages that employ the most sophisticated mathematics and physics, and it operates according to its own order and logic. It is possible to make a virtual space look like a real space, but if you try to force this resemblance, the result will be unnatural and the virtual space will be a sorry sight compared to the real world. But to think that virtual space is inherently impoverished is a misunderstanding, and I think there is certainly the potential to create works that make effective use of its unique order and logic.

Last year in France, during the initial lockdown, CNAP (Le Center national des arts plastiques) put out an open call for a project called Image 3.0. It was co-organized with Galerie nationale du Jeu de Paume, and what they were seeking were completely non-physical works made with the latest digital imaging technology. No matter how much we bring the pandemic under control, for the foreseeable future we will be thinking about exhibitions differently than before, they will be subject to various restrictions in terms of the transportation of works and movement of people, and this project was looking ahead to that future. You might say it was putting a positive spin on the current situation, where museums are all closed and unable to do anything. I submitted a proposal that incorporates an eye-tracking camera, used for video games, to make flames appear to burn only the area of the screen the viewer is looking at. The work was accepted, and I’m now in the midst of producing it. It’s a way of using digital technology to give substance to something that’s intangible, but which we’ve believed is real since ancient times, that is, the gaze.

So, I’ve digressed a bit here, but to answer your question, the four works I’m planning to make for the Japan Society website are also going to be viewable only on the web, not in a physical venue. I intend to make use of that “texture,” which is unique to the web, such as by scanning the work at high definition so it can be enlarged indefinitely and you can see things you wouldn’t be able to see in a physical venue, or making images appear when you mouse over the text, or having images vertically connect or overlap.

|4|

神谷 《Imaginary Landscape》に思いがけなく現れた形や色は、風景のようでも、また抽象画のようにも見えます。モノクロームだけでなく、鮮やかな色も浮かび上がっています。果たしてこれはどんな風に現れてくるのでしょう。描くという直接的ではない方法によって出来上がるこの抽象画制作について教えて下さい。

村上 私は未使用の写真材料をたくさん集めていて、《Imaginary Landscape》ではそのうちいくつかを開封して現像しました。

その中には紙が支持体のものとガラスが支持体のもの、その中間のフィルムベースのもののの三種類あります。感光剤の傷みが激しいものはすぐに現像液に入れてそのまま定着しました。その場合、嵐のような光景が現れることが多いです。感光剤として塗布された材料が長年の温度変化や湿度によって化学変化を起こしたのです。本来ならまっさらだったはずの表面が文字通り豹の模様のように豹変しているのは、時間そのものの物質化のようにも見えます。現像するときの処方などはむろん、当時のレシピに従って自家調合しています。

感光剤の傷みがそれほどでもないものについては、現像液に入れる時に山なみのような痕跡がつくのをそのままにして定着したりしました。写真が今ほど日常的なものではなかった時代の写真材料というのは用途がわりと固定化されていて、肖像写真や風景写真が多かったようですが、山なみのような痕跡を風景に見立てることもできるのではと思い《Imaginary Landscape》と名付けました。パンデミック以降遠出ができない今の状況にぴったりだと思いませんか……。

鮮やかな色の作品は、白黒のガラス乾板でしたが、緑やむらさき、えんじ色の塗料が滲み止めとして塗布されていたものです。現像の工程でこれらは本来洗い流されるもので、しかも、暗室内では基本的に赤色灯をつけて作業するので、最終的な出来上がりは白黒になるそれぞれの板にこんな鮮やかな色がついていることを認識していた人は当時でも少なかったのではないでしょうか。

これらの白黒のガラス乾板の多くは19世紀末まつから20世紀初頭に製造されたもので、マジックランタンと言って、いわゆる幻灯機に入れる種板ガラスというもので、今でいうとプロジェクターで映すパワーポイントのようなものでした。一昔前ですと、コダックカルーセルの中に入れるエクタクロームのスライド、と言ってもいいでしょう。

鮮やかな色面のなかには、大胆な筆遣いを思わせる色むらのようなものもありますが、これは私が塗ったわけではなく、当時の製法でそうなっていると思われます。ガラス乾板の製造はむろん大量生産を前提にした工場で行われていましたが、最終的な仕上がりに直接影響する感光剤の塗布には細心の注意が払われたこととは対照的に、滲み止めの塗料はどうせ洗い流されるものとして、かなりラフに塗られていたようで、工場の従業員のものと思われる指紋も残っていたりします。

人に見られることを想定していないそれらの痕跡が抽象画のようなものに見えるとしたら、それは私たちが抽象だと思うためで、「その抽象は私たちの目の中にある」と言ってもいいでしょう。

|4|

Kamiya In Imaginary Landscape, unexpected shapes and colors appear, which look both like landscapes and like abstract paintings. Along with black and white, vivid colors emerge. Could you please tell us about this process? And could you talk about this mode of making abstract works that does not involve painting directly?

Murakami As you know, I collect large quantities of unused photographic materials, some of which I unsealed and developed for Imaginary Landscape.

There are three types of them: a type with paper as a support, a type with glass as a support, and a film-based type that is a sort of intermediate between the other two. If the sensitizer had been severely damaged, I immediately placed it in developing solution and let it develop as it was. In those cases, a storm-like scene often appeared. The material applied as a sensitizer has undergone chemical changes due to many years of variations in temperature and humidity, and the fact that the surface, which ought to be blank, turns into something that literally looks like a leopard print is like a physical manifestation of time itself. Of course, I prepare the formula for developing myself, according to a recipe from the same period as the materials.

When the sensitizer is not so damaged, images resembling mountain ranges emerge when I soak the materials in developing fluid. Materials from the era when photography was not as common as it is today had fairly specific applications, for example they were intended for portrait photographs or landscape photographs, and when these vestigial images resembling mountain ranges appeared I thought they were analogous to landscapes. That’s where the title Imaginary Landscape comes from. It’s not that I think it’s ideal for this pandemic situation, where we can’t travel to distant places, but…

The vividly colored works were produced using black and white glass plates, but green, purple, or burgundy coatings had been applied to them to prevent bleeding. In practice, these would have been washed away during the development process and, because people worked in darkrooms under a red light, the final result was black and white, I imagine that few people at the time were even aware of these colorful coatings.

Many of these black-and-white glass plates were manufactured in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and they were a kind of negative, called a starting sheet or a seed plate, that were placed in so-called magic lanterns. This was the equivalent, at that time, of showing a PowerPoint slide on a projector today. Or you could say they were like the Ektachrome slides people used to use in Kodak carousel projectors.

Some of the brightly colored surfaces have an uneven color distribution reminiscent of bold brushstrokes, but I didn’t paint them myself; this seems to result from the manufacturing processes of the day. Of course, dry glass plates were manufactured in factories premised on mass production, and while meticulous attention was paid to the application of the sensitizer, which directly affects the final finish, it seems that the anti-bleeding coatings were applied fairly roughly since they were going to be washed away anyway, and sometimes there are also fingerprints that seem to be those of factory workers.

If those traces which were never supposed to be seen by the human eye look like abstract paintings, it’s because we, the viewers, interpret them that way. You could say that “abstraction is in the eye of the beholder.”

注釈

—

Les Rencontres d’Arles(The Rencontres d’Arles)アルル国際写真フェスティバル

1970年にアルルの写真家ルシアン・クレルグらによって創設された写真祭。12世紀の礼拝堂や19世紀の工業用建物など、アルル市内の文化遺産を会場として展覧会が開催される。現在では世界最大規模の写真祭へと拡大し、写真界を牽引する影響力をもつ。2019年には、145,000人以上の来場者を迎えた。https://www.rencontres-arles.com/|back

Note

—

*Les Rencontres d’Arles (full name: Rencontres internationales de la photographie d’Arles) is a photography festival established in 1970 by the Arles-based photographer Lucien Clergue and others. Exhibitions are held at cultural heritage sites in Arles, such as a 12th-century chapel and a 19th-century industrial building. Today, it has grown to become one of the world’s largest photography festivals, with an enormous influence on the photography world. In 2019, it welcomed more than 145,000 visitors. https://www.rencontres-arles.com/|back

—

翻訳:クリストファー・スティヴンズ

協力:ジャパン・ソサエティー

—

Translation: Christopher Stephens

Special thanks to The Japan Society

村上華子「ANTICAMERA(OF THE EYE)」

—

[発行] タカ・イシイギャラリー(2016年)

[仕様] 48頁、図版12点、ソフト・カバー

[判型] H21.0 × W14.8 cm

[価格] ¥3,000–(税抜)

—

以下リンクからも内容をご確認いただけます。

https://www.takaishiigallery.com/jp/archives/14399/

Hanako Murakami “ANTICAMERA(OF THE EYE)”

—

[Published by] Taka Ishii Gallery(2016)

[Spec] Softcover, total 48 pages, 12 illustrations

[Size] H21.0 × W14.8 cm

[Price]JPY3,100. + TAX

—

https://www.takaishiigallery.com/en/archives/17299/

村上華子

1984年東京生まれ。

現在パリを拠点に活動。

—

2007年東京大学文学部卒業後、2009年東京藝術大学映像研究科修士課程修了。ベルギー政府奨学生として渡欧後、ポーラ美術振興財団の在外研修助成を受けてフランスに渡り、ル・フレノワ: フランス国立現代アートスタジオ所属を経て制作活動を行う。村上華子の作品の多くは、写真の古典技法や活版印刷術など、過去のものとされるメディアに焦点をあてた緻密なリサーチに基づいてきた。各作品には、複製技術の起源に関する逸話や村上自身の経験から語られるテキストが添えられ、虚と実、過去の史実と現在の仮説が錯綜する状況が作品の中に生まれている。 主な展覧会として、「From Here to There」ジャパン・ソサエティ(ニューヨーク、2020年)、「La photographie à l’épreuve de l’abstraction」FRACノルマンディ(ルーアン、2020年)、「クリテリオム96 村上華子」水戸芸術館(茨城、2019 年)、「Rencontres d‘Arles: New Discovery Award 2019」アルル国際写真フェスティバル (アルル、2019年)、「ザ・パーフェクト」パリ日本文化会館(パリ、2016年)、「資本空間-スリー・ディメンショナル・ロジカル・ピクチャーの彼岸: 村上華子」gallery αM(東京、2015年)、「パノラマ17」ル・フレノワ: フランス国立現代アートスタジオ(トゥルコワン、2015 年)、「日常の実践」国際芸術センター青森(2011年)、「トーキョーストーリー」トー キョーワンダーサイト(2010 年)などが挙げられる。

神谷幸江

ジャパン・ソサエティ、ニューヨーク、ギャラリー・ディレクター

—

ニューミュージアム(ニューヨーク)・アソシエイト・キュレーター、広島市現代美術館・学芸担当課長を経て2015年より現職。日本、アジアの美術を中心とした展覧会企画を国内外で行う。第12回上海ビエンナーレ「ProRegress」(2018-2019年)、「ふぞろいなハーモニー:アジアという想像物についての批評的考察」(ソウル、広島、台北、北京巡回、2015-2018年)、「Re:Quest:1970年以降の日本現代美術」(ソウル大学美術館、2013年)などの共同展を手がける。「サイモン・スターリング:仮面劇のためのプロジェクト(ヒロシマ)」展により西洋美術振興財団・学術賞受賞(2011年)。

共著に「Hiroshi Sugimoto: Gate of Paradise」(Skira/Rizzoli、2017年)、「Ravaged: Art and Culture in Times of Conflict」 (Mercatorfounds、2014年)、「California-Pacific Triennial」(Orange County Museum、2013年)、「Creamier: Contemporary Art and Culture」(Phaidon、2010年)などがある。

Hanako Murakami

Born in 1984 in Tokyo

Currently lives and works in Paris.

—

After receiving her Bachelor of Literature from the University of Tokyo in 2007, Hanako Murakami received her MA from the Tokyo University of the Arts, Department of New Media in 2009. She continued her studies for a year in Belgium with a government scholarship. With a grant from the Pola Art Foundation, she then moved to France, where she joined Le Fresnoy National Studio of Contemporary Art. Many of Hanako Murakami’s previous works were also produced based on her in-depth research of historical media, such as alternative photographic techniques or letterpress printing. Each of these series of works were accompanied by a text written by Murakami and addressing anecdotes from the original days of mechanical reproduction technology and her own experiences. Her works thus produce situations in which truth and fiction and historical fact and contemporary hypothesis are knotted together. Her major exhibitions include “From Here to There”, Japan Society, New York (2020); “La photographie à l’épreuve de l’abstraction”, FRAC Normandie, Rouen (2020); “Arles 2019: New Discovery Award”, Ground Control Arles, Arles (2019); “CRITERIUM 96: Hanako Murakami”, Art Tower Mito, Ibaraki (2019); “La Parfaite”, Maison de la Culture de Japon à Paris, Paris (2016); “The Capital Room: Beyond Three Dimensional Logical Pictures: Hanako Murakami”, Gallery αM, Tokyo (2015); “Panorama 17”, Le Fresnoy, Studio National d’Art Contemporain (2015); “Practice of Everyday Life”, Aomori Contemporary Art Centre (2011); “Tokyo Story”, Tokyo Wonder Site (2010).

Yukie Kamiya

Director, Gallery, Japan Society

—

Yukie Kamiya joined the Japan Society as Director, Japan Society Gallery in 2015. Previously Kamiya served as Associate Curator at the New Museum, New York, and Chief Curator at the Hiroshima MoCA. She has curated numerous exhibitions internationally focused on art in Japan as well as widely in Asia. She also serves as co-curator for group exhibitions including “12th Shanghai Biennial: ProRegress” (2018-2019) “Discordant Harmony: Critical Reflection of Imagination of Asia” (2015-2018), “Re:Quest Japanese Contemporary Art since the 1970s” at Seoul National University (2013). Kamiya received the Academic Prize from the National Museum of Western Art, Tokyo for her curation of Simon Starling: Project for a Masquerade (Hiroshima) in 2011.

She is one of the contributors of “Hiroshi Sugimoto: Gate of Paradise”(Skira/Rizzoli, 2017), “Ravaged: Art and Culture in Times of Conflict” (Mercatorfounds, 2014), “California-Pacific Triennial” (Orange County Museum, 2013) and “Creamier: Contemporary Art in Culture” (Phaidon, 2010).